So, here I am at last, coming out of the digital woodwork (not to anyone’s annoyance, I hope!) as a follower of Stephen Downes’s “E-Learning 3.0” MOOC. I know, the course is already half-way through — but I’ve been rather too overwhelmed by other tasks to actively chip into the fascinating discussions going on around this platform, until today.

This post is my take on this week’s topic: “Identity.” With apologies for being late to the great conversation.

The Graph

First of all, I’ll present my answer to the task that each of us was asked to complete around this theme, described as follows:

Identity – Create an Identity Graph

– We are expanding on the marketing definition of an identity graph. It can be anything you like, but with one stipulation: your graph should not contain a self-referential node titled ‘me’ or ‘self’ or anything similar

– Think of this graph as you defining your identity, not what some advertiser, recruiter or other third party might want you to define.

– Don’t worry about creating the whole identity graph – focusing on a single facet will be sufficient. And don’t post anything you’re not comfortable with sharing. It doesn’t have to be a real identity graph, just an identity graph, however you conceive it.

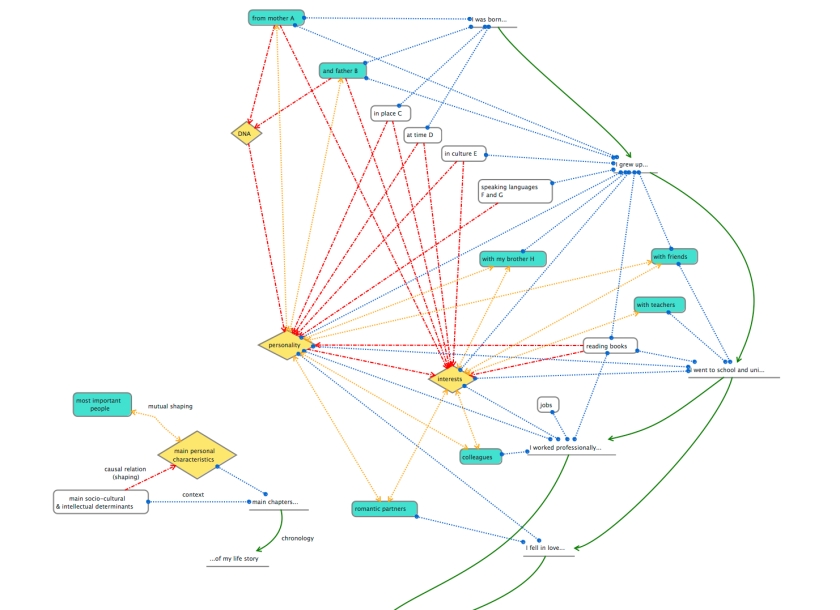

My fellow course participants have submitted many innovative and stimulating graphs (see list here); but I was surprised to find that none of them tackled this question through the angle of processes, evolution, and — yes — stories. Not that I think that this angle, alone, is able to provide a deep and comprehensive image of an individual’s identity — far from it; examining, for instance, the words we use, the traces of our online presence, or the activities we perform, is just as meaningful, and also yields rich insights into the complex topic of identity.

But as far as I’m concerned, my first reaction would be to think of myself in terms of change and processes, informed by experience and other people. I’m not sure why. Perhaps, as an unrepentant Francophone, I’ve been overly influenced by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s famous words:

“Vivre, c’est naître lentement”

(To live is to be slowly born)

At any rate, I think my most natural way of describing myself would be through narratives. So my graph is structured this way.

A few remarks:

– The “Main life chapters” on the right handside (underlined) are just simplified stages of my life. Therefore, I don’t consider them to be “me” nodes exactly — at best, maybe they are snapshots of my ongoing life process and identity. So I think I’ve respected Stephen’s stipulation!

– The “Most important people” and “Main socio-cultural and intellectual determinants” (white and blue bubbles) represent the general context in which my life and identity have evolved, or the crucial elements that have mediated how the process of my life experience has shaped me. It would have been more accurate to display this context as background colors or patterns behind the “life chapters,” but this starts getting really messy. Bubbles “A” to “H” are arguably the most critical building blocks — or bedrock — of my identity.

– In the case of people, I used bidirectional arrows to represent these relationships as processes of “mutual shaping”: not only was my identity continuously shaped and constructed by these crucial people, but I believe that in most cases, I shaped them too.

– I only represented “time” and “space” as factors determining my birth, but it would have been much more accurate to have these contextual bubbles reappear at every stage of my life. For the sake of clarity, I omitted them afterwards.

– The “Main personal characteristics” (yellow lozenges) could be seen as my fundamental traits, both physical and psychological, at any given time. “DNA” and “Personality” are straightforward notions; “Interests” covers everything that drives me, the ideas and beliefs that get me out of bed every morning, and provide meaning to my life. However, I think even these yellow lozenges only provide a partial picture of “me”: indeed, the important people in my life, for instance, are also a crucial part of me. (For a rich discussion of the situatedness of human beings, in space, time, and society, I would highly recommend reading Matthew Crawford’s book “The World Beyond Your Head“).

– My graph, just like Jenny’s, continues outside the frame: this, of course, is to suggest that the green arrow of time keeps on going, and that my identity keeps on evolving. (Were I to believe in reincarnation, the green lines would also have entered the frame from elsewhere.)

– I made this graph using Xmind, although I would have preferred using a 3D mapping software to more clearly map out the various links: as Keith Hamon pointed out, two dimensions are a little too limiting.

Stephen also suggested that we reflect on the following additional questions regarding our graphs:

• What is the basis for the links in your graph: are they conceptual, physical, causal, historical, aspirational?

I suppose the links in my graph are chiefly causal and historical, although some might be considered conceptual (the articulation of personality and interests for instance? but I still think my personality affected my interests more than the other way around).

• Is your graph unique to you? What would make it unique? What would guarantee uniqueness?

A few slight alterations would probably be enough for my graph to describe the living/experiential process of most people on earth (adding/subtracting siblings, educational experience, etc.). However, were I to replace the letters A to H on my graph by the name of actual people, times and places, this graph would undoubtedly be unique to me.

• How (if at all) could your graph be physically instantiated? Is there a way for you to share your graph? To link and/or intermingle your graph with other graphs?

This graph could easily be intermingled and connected with the graphs of the persons I refer to within it, as I already suggest through its “mutually shaping” relations. As for its physical instantiation, depending on how materialistic one chooses to be regarding consciousness etc., perhaps it could be said to be happening right now in my brain as “I” am typing these words. My mind is this graph.

• What’s the ‘source of truth’ for your graph?

Ditto above.

Conceptual quibblings: Quantified, Qualified, Connected

“It’s one thing to want to measure yourself, Mae—you and your bracelets. I can accept you and yours tracking your own movements, recording everything you do, collecting data on yourself in the interest of … Well, whatever it is you’re trying to do. But it’s not enough, is it? You don’t want just your data, you need mine. You’re not complete without it.

It’s a sickness.”

– Dave Eggers, The Circle (2013)

Another reason why I thought of using a narrative graph was that it can be read to mean that identity is also a process of learning. As time goes by, and I experience new encounters with the world, with new ideas, and new people, I keep learning and growing into myself (if that makes any sense?). (1)

In one of her many excellent posts written over the past week, Jenny Mackness cites Etienne Wenger on the topic of identity. I was struck by how closely his description of the concept matches the graph I made — in particular its social aspect:

An identity, then, is a layering of events of participation and reification by which our experience and its social interpretation inform each other. As we encounter our effects on the world and develop our relations with others, these layers build upon each other to produce our identity as a very complex interweaving of participative experience and reificative projections. Bringing the two together through the negotiation of meaning, we construct who we are. In the same way that meaning exists in its negotiation, identity exists – not as an object in and of itself – but in the constant work of negotiating the self. It is in this cascading interplay of participation and reification that our experience of life becomes one of identity, and indeed of human existence and consciousness.

Of course, the idea of using narratives to tackle the notion of identity is far from new, and much has been written about this in various academic fields. I am not well acquainted with most of them, but this article provides quite a comprehensive outlook of these matters (I particularly like this quote: “our narrative identities are the stories we live by”). See also Wikipedia on “Narrative Identity“:

The theory of narrative identity postulates that individuals form an identity by integrating their life experiences into an internalized, evolving story of the self that provides the individual with a sense of unity and purpose in life.

Now, taking “identity as a narrative” as a starting point (again, other theories may be just as valid), what should we think of the notions of “quantified self,” “qualified self” and “connected self” that Stephen refers to in this week’s featured article?

I must confess feeling a bit confused as regards how to handle these various concepts. To start with, are they ontological, epistemological, or both? In other words, do they refer to a self that exists because or inasmuch as it is being quantified, qualified, or connected — or to a self that can be known through quantification, qualification, or connections? I’ll go out on a limb, and guess that Stephen is viewing them through the twin lens of distributed knowledge and connectivism — according to which learning “is the network,” AS WELL AS “the ability to construct and traverse those networks”… But I could be wrong.

So let’s just assume that these notions are both ontological and epistemological: we are talking about a self which exists through these numbers, words, and connections AND which can be known through numbers and/or words and/or connections. (2)

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves!

1. The Quantified Self

First, how are we to distinguish the “quantified” self from its “qualified” and “connected” avatars? Jenny wrote a very insightful post on this topic. Like her, I think of numbers and analytics when reading the words quantified self — and Wikipedia agrees.

The notion of “quantified self” has notably been championed by a Californian company; nowadays, the chorus of “self-knowledge through numbers” is being sung by millions of “self-trackers” all around the world, to the extent that this set of practices is even being referred to as a “movement”…

In the introduction to The Quantified Self, Deborah Lupton defines “self-tracking” as “practices… directed at regularly monitoring and recording, and often measuring, elements of an individual’s behaviours or bodily functions,” and “the quantified self” as “using numbers as a means of monitoring and measuring elements of everyday life and embodiment” as well as “an ethos of apparatus of practices that has gathered momentum in this era of mobile and wearable digital devices.”

These practices have indeed been proliferating over the past few years (a quick glance at the Google or Apple store is enough to get an idea). Perhaps this love story with our numerical mirror images dovetails all too well with at least two co-related phenomena: the bureaucratization of society, and the omnipresence of smartphones and other “smart” devices in our lives?

We may also detect, in another of Lupton’s descriptions of the practice, a particular mindset that bears the hallmark a puritanical, capitalistic mindset (as described most famously by Max Weber), and which may have reached its most apoplectic expression in the neoliberal era:

“Indeed the very act of self-tracking, or positioning oneself as a self-tracker, is already a performance of a certain type of subject: the entrepreneurial, self-optimising subject. A fine line must be negotiated, however, in seeking to perform this subject position. Too much focus on the self may be interpreted as self-obsession and narcissism, while too little signifies failure to conform to the idealised responsible citizen who is actively seeking out information as part of the project of taking control over her or his life.”

So the self-tracking impulse also reflects the urge to self-optimise, and be one’s own boss — stern, responsible, in control… “fitter, happier, and more productive”.

German sociologist Helmut Rosa also contends that self-tracking is bound to be disappointing: while it aims, as a practice, at measuring and improving a person’s quality of life, in the final analysis it ends up having a self-reificating and alienating effect (Kappler et al., 2018).

Quantifying our lives definitely has its pitfalls, to say the least — and this goes beyond the realm of mental sanity. As Lupton observes in the introduction to her book, the personal data that is collected is

“now typically transmitted to an stored on cloud computing databases. As a consequence, accessibility to these details is no longer limited to the self-trackers themselves, as was the case in the days of paper journals and records, but personal details are potentially available to other actors and agencies”

— such as data-mining companies, hackers, or government agencies. I’ll return to this later.

And in the words of Btihaj Ajana, who edited Metric Culture: Ontologies of Self-Tracking Practices:

“We are indeed living in what we can call a ‘metric culture’, a term which indicates at once a growing cultural interest in numbers, as well as a culture that is increasingly shaped and populated with numbers… What is striking above all about the current metric culture is that not only are governments and private corporations using metrics and data to control and manage individuals and populations, but individuals themselves are now choosing to voluntarily quantify themselves and their lives more than ever before, happily sharing the resulting data with others and actively turning themselves into projects of (self-) governance and surveillance.”

2. The Qualified Self

What about a “qualified” self? Would this notion discard the realm of numbers for that of words and stories?

Discussions on the notion of the “qualified self,” as my fellow EL30 participants have noted, are few and far between – and tend to revolve around the eponymous book by Lee Humphrey — in which the author makes the case that selfies and photos of our everyday meals are just modern instantiations of the age-old practice of diary-keeping. (Except for the fact that diaries were meant to be private…)

In fact, I was surprised to notice that when people do write about the qualified self, they seem to view it as simply meaning interpreting the data collected by self-trackers…

As Jenny Davis observes on her blog:

“Specifically, it seems that self-quantification has a really important, prevalent, and somewhat ironic, qualitative component. This qualitative component is key in mediating between raw numbers and identity meanings. If self-quantifiers are seeking self-knowledge through numbers, then narratives and subjective interpretations are the mechanisms by which data morphs into selves. Self-quantifiers don’t just use data to learn about themselves, but rather, use data to construct the stories that they tell themselves about themselves”

She then goes on to state,

“Self quantification is a process bookended by self qualification. Yes, the numbers are important. Self-quantification is, by definition, self-knowledge through numbers.”

Likewise, designers Eric Boam and Jarrett Webb believe that

“Where the quantified self gives us raw numbers, the qualified self completes our understanding of those numbers. The second half completes the first half.”

As for Mark Carrigan, he defines qualitative self-tracking as follows:

“Using mobile technology to recurrently record qualities of experience or environment, as well as reflections upon them, with the intention of archiving aspects of personal life that would otherwise be lost, in a way susceptible to future review and revision of concerns, commitments and practices in light of such a review”

And yet, the two examples he brings up to illustrate this practice — compiling daily lists of accomplished activities, and counting the number of days spent working on a book — are similar quantifying processes of counting and listing.

So the qualified self seems to be viewed not as qualitatively different from the quantified self, but merely as an extension thereof. It’s, at most, self-reflection built mostly on quantifiable data.

Stephen Downes, in this week’s article, seems to have a slightly different approach: he posits that the qualitative self is built on the statement of facts about the self, and by “facts” I assume he refers to the “properties” defining a person (such as “I am from country X,” “I worship god Y,” etc.). Such facts appear independent from analytics, so this view doesn’t seem to fit so well with the other definition of the “qualified self” outlined above.

3. The Connected Self

As for the concept of “connected self,” it seems to have been even more rarely explored, and then, so far, only in the fields of: neuroscience; genetics; feminist theory; and theology. Thus, apart from the neuroscience approach (“the self lies in the totality of the brain’s wiring”), there isn’t much for us to chew on as far as the issues of identity and e-learning 3.0 is concerned. (Maybe the “connectivist self,” as a notion, has been more commented on?)

Of course, you might say that this entire section hasn’t had much to do with e-learning anyway — but please bear with me! I’m getting there.

Our Fascination for Numbers

“If the art of storytelling has become rare, the dissemination of information has played a decisive role in this state of affairs. Every morning brings news from across the globe,

yet we are poor in noteworthy stories.”

– Walter Benjamin, “The Storyteller” (1936)

This week’s topic being eminently philosophical, I couldn’t resist the allure of a little rant on statistics as related to self-knowledge.

Stephen Downes proposes that

“knowledge about ourselves, our associations, and our community will create an underlying fabric against which the value and relevance of everything else will be measured. Instead of demographics being about quantity (sales charts, votes in elections and polls, membership in community) we will now have access to a rich tapestry of data and relations….

“we will have an unparalleled opportunity to become more self-reflective, both as individuals and as a community.”

I do like the idea that data, particularly of a digital type, could be empowering to the individual and society. I have personally benefitted from generating electronic data about myself on some occasions, be it as statistics for my sports training, or as video recordings when I played in a drama club. There is no doubt that technology can help individuals increase their level of scrutiny over their own activities, and thereby, help them progress. It’s true of writing, as it is of gathering data on a smartphone.

(although I would also point out that much of this kind of software or technology replaces to some extent people we would have collaborated with in the past: a friend to give advice on our acting, a coach for personal training, etc.)

From the political standpoint, information can also be crucial for ordinary citizens or communities to know about the activities of more powerful people, which is what makes a free press so important. Likewise, the internet and mobile devices can be seen as connecting an ever growing number of people, and making “information” more widely available (let’s not talk about fake news…).

However, I am quite skeptical that access to more (and/or better “qualified”) data since the advent of the “quantified self” has served a meaningful role as regards the particular issue of self-knowledge. The reasons are threefold:

1. Insignificance

Some argue that through more self-reflectedness, our data will help us better understand ourselves. But I fail to see what sort of personal or collective data our connected devices will provide that will really be of such precious use.

Indeed, what kind of information can the future, all-knowing graphs provide me about myself that is both, a. of crucial importance and b. currently elusive or difficult to know? The number of times I clear my throat in the course of an afternoon? The number of kilometers I drive per month? Whether I generally project confidence or awkwardness in speaking to others? Whether I happen to cross in the street, rarely, sometimes, or very frequently, attractive people of the same zodiacal sign as mine?

In brief, I cannot imagine any personal feature so important as to warrant a complete re-understanding of myself, or at least a fundamental reassessment, that prolonged, earnest, relentless scrutiny and introspection cannot already produce. Taking my identity graph displayed earlier in this post: I don’t need a smartphone to know about any of its components. And while a mind-mapping software makes it convenient for me to present this to people, I could have done so with no more than a piece of paper and a pencil.

2. Data ≠ Reflectiveness

There is a reason why the maxim “γνῶθι σεαυτόν” (Know thyself) was inscribed on the portico of the temple of Apollo. Self-knowledge, in a deep and meaningful sense, is difficult. It is a slow and uncertain groping in the dark, which requires introspection, self-awareness, sensitivity, and a good deal of emotional intelligence. How could more statistics make this learning process any easier?

This is especially the case if one tends to view narration and stories as ways to construct our identities (as I do). Machines and sensors can provide us with avalanches of data — we may know exactly how many minutes of sleep we get per night. But can they help us form more meaningful accounts and stories about who we are, and what we have lived? Can they make us more thoughtful, attached to the pursuit of truth and meaning? Or instead, do they lead us to ever-more entranced forms of self-gazing in front of our screens, checking our own stats, keeping track of hours, minutes, seconds, kilograms, blood pressure, number of steps, number of days spent writing book X…?

I could have all the data in the world about myself, and still struggle to make any sense out of it at all — or be too distracted to pay it any deep attention.

3. Everything you log will be held against you

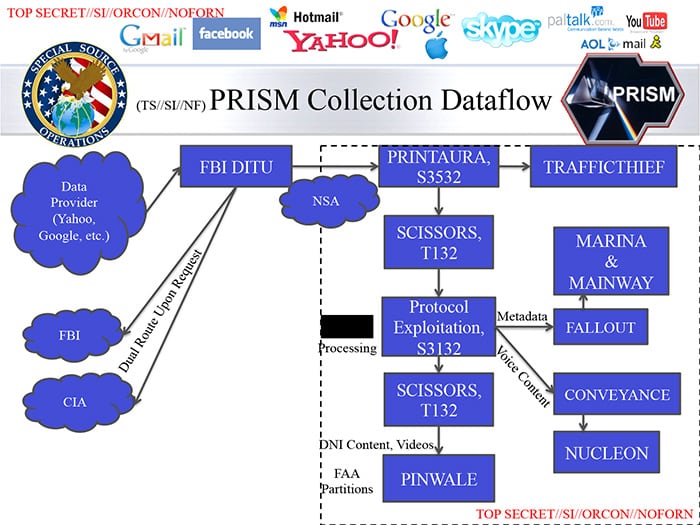

In the final analysis, it seems to me that these infinite bits of data “like stars in my pocket” are bound to remain most primarily and immediately useful to the sinister forces that already harass us: advertisers, political influencers, and panopticon-like, spreading systems of mass surveillance. To these data barons, every supplementary bit of info on anyone is another access point through which to reach, control, penetrate, and target this individual’s behavior, freedom of action, social circles, access to facts, and even beliefs — or their life.

Of course, it feels almost trivial and commonplace to hold forth on such things nowadays; but I think it’s still worth hammering this home.

Indeed, I am a little surprised that there has not been more emphasis, in the texts and blog posts I read this week, on this other term for “identity” that has been gaining a lot of traction over the past decade: “metadata.” This is how surveillance agencies around the world refer to the individual characteristics (owner of cellphone, located within X meters of terrorists Y and Z, US Air Force drone missile target #3566…) that may warrant a person to be imprisoned, or even — increasingly — shot dead. (3) Be it in China, in the US or in Afghanistan, personal data and control thereof has been largely, and horrifyingly, disempowering for the general public lately, rather than the opposite.

So, no matter how we frame the benefits of a “qualified” self, reflecting on these issues confirms me in my high reluctance to engage actively on the biggest social media platforms and to keep disseminating more reflective bits of myself. Even supposing everyone’s identity were to be protected behind the supposedly bulletproof doors of encryption — as Stephen Downes points out toward the end of his video: who controls the castle? And how long before we are compelled, by law, to have and use but one, single, officially registered open public identity online, confirmed by biometric means – instead of being able to create innumerable anonymous, or less public, accounts?

It seems all the more challenging to imagine the “connected” self as being better able to control (both in terms of power structures and technical complexity) matters of personal privacy, when projects like Solid seem far from being enthusiastically embraced. (4)

Instead, it is much easier to envision the “Connected Self” as logging in through… An omnipresent Facebook login, similar to the software provided by the Silicon Valley company described as an all-knowing global Leviathan in the novel “The Circle”. Who will be manufacturing everyone’s physical pass key in the future? These sacrosanct “public and private keys” (and use thereof) are quite likely to become an object of increasingly tight scrutiny and control, especially on behalf of government — just like the usage of VPNs is so tightly monitored in countries like Iran or China. (5)

In sum, you’ll understand that it’s much harder for me to be as enthusiastic as Stephen, who perceives in the evolution of the “connected self” an “unparalleled opportunity to become more self-reflective.” I think the gaze will mainly keep coming from outside, from everywhere at once, continuously, relentlessly; not from our own eyes in the mirror — or if so, it will be the dull, drugged, fascinated eyes looking back at us from the surface of Narcissus’s pool.

FOOTNOTES

(1) Stephen Downes himself has referred to the concept of “learning by growing” (personally, and/or neurologically) on many occasions in his writing. For instance, here: “We learn, in connectivism, not by acquiring knowledge as though it were so many bricks or puzzle pieces, but by becoming the sort of person we want to be” and there: “To learn, one does not simply ‘acquire’ content, one grows. To learn is a physical act, not a merely mental act.”

(2) However, to be honest, the second option seems much more interesting to me within the context of a discussion on e-learning and personal growth… An ontological tack would suggest that different selves cohabit inside of us, whereas I think the epistemological approach simply states that there are various ways of getting to know one’s single self, or identity. It is certainly convincing to imagine that a government or an online advertiser has chiefly access to a “quantified” version of me, while my family and relatives would presumably know me through other methods than hard data; but in both cases, there would only be one “me.”

(3) See this excellent summary of the “Drone Papers,” and Vice’s shorter presentation.

(4) Solid’s founder, Tim Berners-Lee, has launched a start-up to reap financial benefits from “the new web built on Solid”… So maybe he, for one, believes in the project’s success? But the decentralized, free, utopian spirit of the late 1990s seems increasingly far from sight.

(5) One day, as I was getting steadily drunk at lunchtime in a restaurant of the north-western province of Xinjiang, China, I was randomly introduced to someone who worked in the Cyber-Intelligence Department of the provincial branch of the People’s Liberation Army (?!). Over more drinks, he assured me, very good-naturedly, that he could track in real time who was using a VPN software at this very moment, throughout his immense province, and locate them precisely. That was in the summer of 2016, 12 years ago. Talk about now… The state can know in real-time the identity (the full social graph!) of every person walking in the streets of certain cities, every single one — through AI-powered facial recognition.

There’s such a lot in this post that it’s difficult to know where to comment – but I just wanted to say thanks for sharing all these thoughts. You raise some interesting points about the qualified self and connected self. The shift from quantified to qualified to connective self as a way of defining ourselves and our digital identities does seem central to E-Learning 3.0. Your post has got me thinking that maybe to fully understand all the ideas presented through the weeks of the course, I will need to try and connect all the key ideas. By this, I mean that I am beginning to think that ideas such as the qualified and connected self cannot be fully understood independently of what has gone before in the course or what will come after. Hope this makes sense. I am thinking aloud 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jenny, thanks for your comment!

Yes, I am also curious to further explore these notions of “self” – in particular, the “connected self”.

I wonder if Stephen’s vision could be brought closer to Charles Eisenstein’s concept of “interbeing” (https://charleseisenstein.org/books/the-more-beautiful-world-our-hearts-know-is-possible/eng/interbeing/), or Jeremy Lent’s thoughts on the “holarchy” of personal interconnectedness (http://www.liology.org/dynamical-systems-theory.html)… Although addmittedly, these take (I suppose) a more moral and even spiritual starting point, while Stephen seems to focus more on the philosophical and practical aspects of being “physically” connected through IT networks.

Let’s try to keep this discussion going as the course continues!

LikeLike

Hi Dorian – I don’t know the two references you have linked to, so I’ll look forward to following up on those. Thanks. I am also interested in Iain McGilchrist’s work on the divided brain (that is an over-simplification of what his work is about). I think Stephen’s work on connectivism resonates with McGilchrist’s notion of ‘betweenness’ (which similarly discusses how everything is interconnected) – http://Iainmcgilchrist.com. I have tried explore this in a couple blog posts, i.e. McGilchrist’s work on betweenness, but I have yet fully understand it all – or connectivism!

LikeLike

And also – thanks for all the links to additional resources. Very helpful.

LikeLike

Hi Jenny,

I have just read your blog posts on “betweenness.” Fascinating. I will also take time to read the article you recently co-wrote on open online education, as I am very interested in the process of learning over social media as part of my own research.

I noticed that in your first post on betweenness, Gary Goldberg references Charles Eisenstein too, which doesn’t surprise me! His notion of interbeing does seem very close to McGilchrist’s betweenness.

It also looks like I should read a bit more into the work of Deleuze and Guattari… So much to read, and life is so short!

LikeLike